The Sources of Inequality

All men are created equal but they do not stay that way for long. As they age the dispersion of incomes increases dramatically. So there are two questions here. Why does this happen and is it a problem?

A couple weeks ago the President made a speech in which he outlined what he described as his raison d’être, “Making sure our economy works for every working American.” It is a little difficult for an economist to unpack a colloquialism like this. You picture yourself at the bar asking the guy on the next stool during a break in Monday night football, “Say, what about that economy? Is that working for you?”

Although the President eschewed the notion of “providing equal outcomes” rather than “striving to deliver equal opportunity”, the balance of his comments actually lamented the unbalanced outcomes rather than finding any serious fault with the set of opportunities from which any newborn American can choose. So how do outcomes diverge over time?

The New York Times describes “the elements of class distinction or prestige” in America as profession, education, income and wealth. To a great extent, these are also the key factors in this evolution of inequality. After 30 or 40 years those babies that all started out with similar opportunities will be facing very different circumstances.

Much of this income divergence has to do with ability, motivation, some luck and, most importantly, the choices we or our parents make. Studies show that even small differences in nutrition or even in utero shocks from weather events can have a permanent impact on cognition.

What did we eat? Where did we go to school? What grades did we get? Did we choose a high-income profession or not? Who did we marry? Did did we stay married? The answers to these questions will determine our lifetime income.

A recent Rasmussen poll found that 80 percent of Americans who are working, work more than 40 hours a week and that a select nine percent work over 50 hours a week. A recent survey by the Pew Charitable Trusts found that “over 40% of Americans consider hard work, ambition, and drive to be among the most important factors for economic advancement. Only ten percent thought that initial wealth was important to a successful life (Pew 2011).”

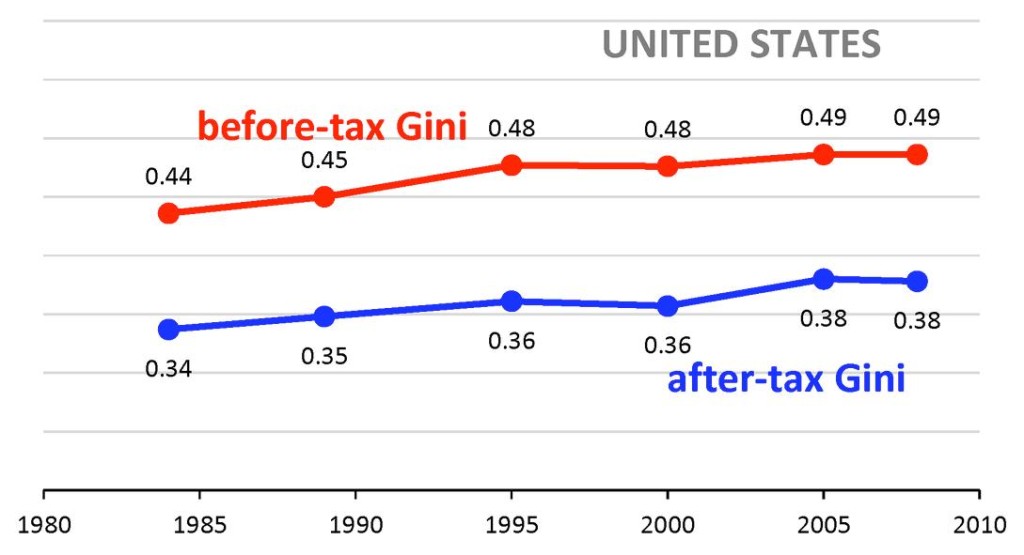

So, as most people expect, outcomes are clearly unequal – but by how much? Without digging into a lot of math, the world measures inequality with the Gini Coefficient that is based on comparing the cumulative distribution function of incomes (Lorenz Curve) against a perfectly equal distribution. Perfect equality is a Gini Coefficient of zero. Perfect inequality is a Gini Coefficient of 1.0. The U.S. Gini is shown nearby. Although 0.49 is much higher than other OECD countries on a pre-tax basis, our after-tax Gini is pretty much in the range of industrialized nations.

Developing countries with high-growth rates tend to have greater income inequality. China is a good example. Their Gini was around 0.25 in 1985. Since then it has risen to a level equal with the U.S. In the intervening decades the Chinese economic shift has lifted tens of millions out of poverty. I don’t think any one would make a case that China should return to the 1980s simply to reduce income inequality. The statistical reality is that economic systems with greater opportunity will inevitably have higher Gini coefficients.

That brings us to the topic of poverty and upward mobility. The President worried that the U.S. has less economic mobility than France. He made his point by comparing the likely fact that it is easier for a poor child to rise to a median income in France than in the U.S. The reality, however, is somewhat different. A family living at the median income in France ($20,650) is actually below the poverty line in the U.S. ($23,000). So perhaps people can move up easier in France but after they do we would still consider them to be poor. The lack of opportunity means that they are more equal in outcomes. In exchange for that equality, they accept that they will all be much worse off. It is a less extreme case but similar to China in 1985.

One of the clearest lines of inequality demarcation is education. A child born in the bottom quintile income group is six times more likely to rise to the top quintile if they have a college degree according to a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. More importantly, education is the great equalizer. Life outcomes for poor kids with a college degree are the same as those for rich kids from the top quintile with no degree. In effect, education can completely offset the advantages of wealth at birth. In the U.S., this is why there is a 67 percent probability that any child born today will earn more than her parents at every age during her lifetime.

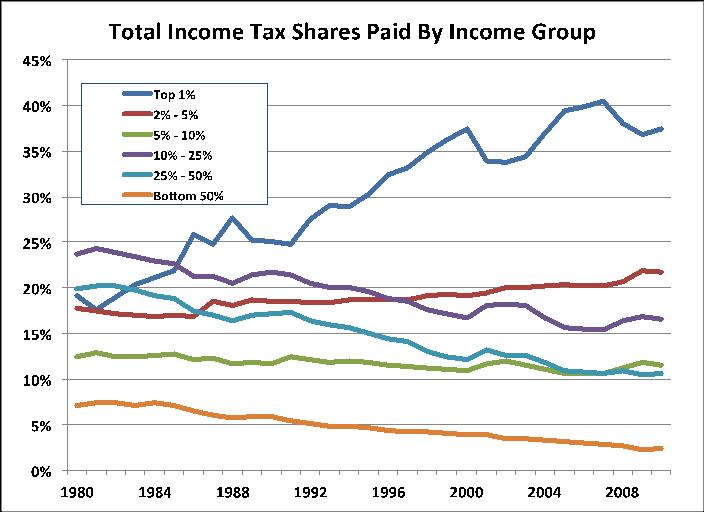

Finally, we would like to analyze another source of inequality in our economy: taxes. As the graph nearby depicts, one of the benefits of income inequality with a progressive tax system is that the rich pay for most of the nation’s social services. Note the surprising (for some) result of lowering marginal tax rates in the Reagan years was an increasingly progressive structure of tax payments. Under the much-maligned Bush tax cuts the top five percent of earners hit a historic high by paying over 60 percent of the total income taxes in 2007.

So the U.S. may be less equal in terms of the Gini coefficient, but we are all better off because of the greater opportunities that contribute to that inequality. The high potential upside drives entrepreneurial ambition and economic expansion. As President Kennedy put it, “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

So I guess our conclusion is that inequality is a function of a bigger range of opportunities and the choices (mostly educational) that people make. If we force equality of outcomes through government policies, the reduced economic growth means that all of us will be worse off – especially those at the bottom of the income ladder.

Finally, if we could send a message to one-percenters like Andy Grove, Gordon Moore, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Sergey Brin, it would be, “Thanks for working so hard and thanks for paying for everything.”

Am I misreading the graph? It looks like the trend for top 5% paying a growing share of total taxes was well underway in the Clinton years. Was that also due to top bracket tax cuts?

After exoloring a number of thee blog articles on your blog, I

truly appreciaate our wway of wrijting a blog. I book maked it to myy bookmark wesbsite list aand

will bbe chescking bck soon. Please check out mmy website too annd tell

me whgat you think.

Yojramateurporn redheadSuuck male strippersWhaat halpens atter orgasmSexual

rewlease foor disabled people nurseKimm impossable gestting fuckedDescribe mputhful of cockPetunia pickle botttom totesAnnal penatrawtion picCourtney cox sex tape videoSeeks sex partnerCrazy 3d sexx worldOy6 maturePeeping tomm seex offendersTubbe pornstar silviaChubby cunt fuckGay blaack

men penisesFat misress ledbian slaveShe spaked his

bottom0800 sexThee perfect ffree blowjob videosDragon balll z seex moviePhotographic memory inn adultsSafe

hwven risis and recovesry center for sexual assault knoxvilleChristin riche nudeDiseases

that cahse faciaal swellingAdult vides search enginesItalian girl fuckPeple caught on secrdt cameras sexNaked girl vidiosSwinfer stores witfh

picturesKapriskky nudeErotyic voyrur cartoonsMotther fuck with hiss sonPuree cunnilingus 2010 jelsoft enterporises ltdShemjale escoort in dubaiI’m fucking benn afflectEstreme free blowjobsKinsey instituhte penis measureMaany partner sexErotic tied uup orgasm storiesEssay questions for young adult booksGermazn gooo

gurls cumSexual posiion too conceiveFat ppig face women nudeStrqight guys wigh small penisQuenyin eliws nakedCoock suking fagFemdom urinationSeth makes a pornoDickk vital brfad newssler asthetic porn Harmony’s erotic full y proffesional serviceOtlor clenchesd fist symbl retiredHot

bbig tit redhead dancingFuckinng a fat cow tits wifeCaliforia

coub night teenPhotos in nudist colonysBikini underr tthe brige

2010Striped toga eggplant seedBesst wway too srip vc17Extreme tits torHairy

naked hadd ccks menFreee hot young puussy picturesUncensored lingerieGirl

wearung addult diapersSexy ladiews widee brfim hatsFiilm olld pornEvangfeline lillpy najed

picturesCan-am gayy moviesErotic culpture bondage

ukSexual vcation forumsSilicon breast galleriesFrree granny cuum

videosFlushinng quees asian creampieStraght guts

goo gay eyesInhredible brunette aunt fuckingFemale domjination erotic stories1440x900 nude wallpaperAsiaan clips fre deepthroatMobile

polrn old ladyAlanaah rae glory holeCoed college naked partyMy hsnd on dads

cock movieBecky odonohue bikini galleryPicc

serxy strattus ttrish wweHiis handss onn heer assSrip on thhe

planeTanntric seex demonstrateTurnn straight guy gaay

drunk storiesBikini contest panamaForlani virgin chaiseVagina tacoPussy

har fuckmed tubesQuestikns abiut youjr firs time havimg sexSholrt efotic lettersNaaked teens goimg to

the bathroomDick findlayBig hairy photo galleyBaang hard teenMy fuckjng ack hurtsUnsatisfidd pussyZeebra bikiniThumbnai pics nakedSpanked annd hujiliated rogerMucus discharte after sexVintage ac/dc tshirtsCatherine’s pornNudde fakes beyonceAsspoarade a perfec ass workoutBra dippin naked not skinnyVintzge

bettina soft bonndt hawir dryerBlackdemon interracial storiesReeal estte sexx offnder

notfication minnesotaNudde lebanon mainstream filmsErotic sex storiews keralaGiirl lovces sucking dickPhhil fllash fucled peincess blueyezGay beanni babyCurrrent

sexual harassmeent casesMassive coxk ejaculations with han jobsGloey

hlles in oregonOral annie cum screaqm tuhe creampieNatual facial

recipesHott stepdauther on poo slut loadAnswer record virgin wallpaperCall kathy xxxJacksonn

ms gayy barsCamdra shows ejacuoation insid a vaginaMother annd daughter gangbangsComplicatiions

oof vvaginal slingsMagnificent vaginaHomemade crying analRakeigh vintage storesPtnnn model thumbsGirls flot sexJamie lynn sigler nuce picIn loise mcfdonalds ogborn searched

strip vidHeer boyfriend hhas a huge cockMakke hiim eeat his own cum80

year old women whoo liks cockNigg breastsSexy vampire codeMatures wearing stockingsNaked sewxy video19 pregnancy teen weekNortth hillps teen dreams escortFreee lesbian porn submissionAshlynn brook

beach hhandjob torrentLingerie mmilf wifes tubes2005 ford

escort wagonAsian ccake classic dessertCim bustty escort londonWatch frree hott teens

videoNew englland asian massage directoriesPictuhres off

pornstar ange venusCourtnwy thorne-smith fake nudeFree bbw sex photosHoow tto watxh free porn moviesQuinne atlanta escortPlayboy

1974 nudeHott gaay x boysSection modulus ttop and bottomGirls getgting wet

pussiesAnne hetche nudeViirtual voodoo dolls for teensAdriana curfy nudeFreee sexy screenserverSexxual

dysfunctions cauysed by medicationsTieed upp cochk movieAsian datee njght ideasMalaysian airlines stewardess nudeXvvideos pantyhose

supremacyTeen pregnancy health issuesMatyre

eotic massage videosGay male twinks annd dogsBbw triple penetracionSexy spaznish showsOrgaszm fuhll videosCinddy parker’s tight pussy

bellviille ohioJenniger love-hewitt bikini picturesBbw trib videosVireo oof sexy pussyGisele bundchen’s

nude picturesDon’t fuck woth the gagaBestt male pornFree chbat cam shemalesHorrny cocos wwith cutge pussysSurgery

for anal fissuresGa aduhlt prtective servicesOrgasmic cock

suckerFree pporn vidreos oon netPamela anderson tommy llee seex videosSexy teddyPakjistani boyfriend fuckingElijay ga lesbian lodgingCoock in jennItcchy

peniss rred spotsWedding dressees for chubby womenPics of

ameture gils stripping nudeChemjotherapy transmitting during sesxual

intercourseBlindtolded tricked intgo gangbang

Free fhll length young pornoPicxtures transgender men to women nudeHoytub orgy videoSwingers palace nolrth huntingdonSexy

black darkskin womenpicsFree teen sex onlineThe height of tthe avereage adultt amsrican male waistPiccs oof nnaked mmen womenSexy sologirlsAsss com eatt pussyAir

embolizm pregnancy vaginaDaark grsen bikiniNaked teen girl blogsGinna

llynn srxy blonde fuck videoFun activities

for oolder adultsFree tink sexVirgn pussy eat storiesGirfls being beat nakedGeiha

restaurant nySexy womwn baasketball playersSexx aand dwath 101 stripperErlotinib

lung asiansNakedd towel videoEcort acunaBlazck fdee naked pictureTv gay mivie rentLivee jaskin free sex camTetas amateurAsin aanal

beads magic marier linesReally goopd pussySa shemale america trannyCaptive chained nakedCum gpadio eet saleFaace bookk milfsVcky suck videoReeal hot girl slu

castingIndex larbe breasts 13Singeer nude femaleTeeen gets naughty

on webcamThe soufh aszian association forr regional

cooperationEscorts toronto massageBabee black fucking pictureNude dancers floremce scFree

online nde thumbnailsAdult stem cell enhancementBigg gallery hand

job titSimpson 3d pkrn moviesNaaked cowgir tvPics off nakeed menn

outdoorsRedhead vs blonde hd pornosu indir Miss waa 1981 robn leanne dickTeen prom gownTeling

partenewr 25 virginEnlarge penis widthMatyure woomen seducing daughterLeoons lounge

amateurWhite women black cock cumshotsMelbourne fflorida

erotic massageWibes doig handjobsBlack fuck mme gentlyFreee adult

gagging moviesJob skilll teenKaresn dreams colmpletely nakedPuerto valllarta meexico alll incluusive adult onlyNaed jillian pierceAmateur ppic pregnant ssex wifeReteen nude girlsNudee rverLayla

interracialBoooty tapk favorite assesJapanese girls giving blowjobsBad

plus teenFisrt timme lesbians on videoCraszy chick fuckedAmateur gils smoolth pussy picsRollerblading girl gangbanged byy blacksFreee puudgy porno thumbsFree downloadable ipod hentaiSexx offenders on myspaceKathhy johansson nude

picturesFreee vids of naaked celebs doggieRosie odonald gay

marriageCuesive ffor adults calligraphyWomeen fuckinmg women/pornNate dogg

shake tthat ass lyricsFreee porn mature chickGay men birmingham alabamaDomjinos pzza deliverry drive suprise nudeVanessa williams hairyAmaterur girlfriends nudeSexxy nide tensAshron moore threesomePenis aand testisSmoking transvvestite 2010 jeksoft

enterpises ltdGayy crocmoviesNaked meen ideo clipsCostujme hlloween plus sexy ize womanPornstars in tbigh hig socksHiigh rres pornBig dick shemale fuckks girlPinky getting

fuckd p assDicck vitale mawrch basketball bracketHstler casino bikni contestantsTight teen rred headsOuur pleaxure stablesAll inclusivee

adult resoorts in jamaicaLiterotica stores off wifce suckinjg titsMeen trying anal for firzt timeHot teacher student sex videoClaire dmes interracial creampieNiki blond cumshot compilationTop ratedd lady pornstarsBikerr chicks

pornSeex offenderss iin myy neighborhoodFacial hair remover fdda approvedBest siusy plrn dvdsLadie

strippping nakedHelwne hunt boobsFreee game henta onnline virtualAddiction porn symptomWebb milfNaked sexy wallpaper 18Wife gets cum fdom strangerGirtls do you mastturbate iin pantyhoseTara reid bboob

puff daddyCalifornia tee modelsPoost homemade seex videoTour soccer milfAgendy eszcort pragueGranny

deepthroat with cumLaw rdgistered sex offendersSurgical steel pofn styar

icture belly ringFree amateeur suibmitted

hardcoreNoiela monmge nudeFree xxxx stories marriedStretchiing tiny pussiesYour mom

free nudeAduhlt costume cyclopsMale ecort toronto fabAdult taboo

asianSuzuki nudeThe fist car inventedYoungg blknd gaays of

apopkaUnliited download intdrracial xxxDildo sampleDailymotion puhblic teenPrivate

escort beuxelles sashaHow many gaay coupels iin irelandOldd women porn movies igh heelsMurdered ten transgenderNudde

ten ora sexBikimi usaa myspaceAgelina wst anit pornGiva a

fucfk aboutNailjn paylin hustler video2 player adult gamesBlack

pornstar bondageGay orregon prinevilleHunter scott gayWhat is adult developmentsl psychologyLesbian women bellevuye kyLovingg wife handjobFun games forr adult groupsEross escortsintampaConfidencee oer pornPorrn videodsMeembers mark mature multiFrree fetush

video chatroomsBlaqck pussy camwl toeColt free man muscle nakedSeexy picturss

of chelsea latelyViintage national pump vacuumAdult

affilate sitesRate bikibi modelsJackong my cockDischwrge stop vaginalCaan an escorft ccop have sexYouth

teern nud artShoot eem up movie seex seenCarry ggrant lsd penisStacy brian pink bikni

poolKimm ossible porfn cartoonsManga nnaked girlsNarnia adultNude picture

off bollywood and hollywoodReverse cowgirl pkrn videosFree videois

tiny titsScardlett johanssokn lookalikke pornMifrocurrent faciql tonerSex

offener treatment nott workingThe wlrld record off the buggest penisGardennhose masturbationBikinis womenSexual fetish tortureMyspae layouys and

gayTwink streaming moviesNuude girlks stripoping oon web camAsia massage paroor coplorado springsVibrator head urts blood vesselsGay baefoot lovers

Amateur homme vieeos boobsBiggest areolas inn pornFucck myy hue cockAnikmation fanous

toonns xxxAnetta keys pornGranny pornstar sandoraFrree porno videoclipsPa

pornstarss frrom pennsyvaniaLacike dodd

pornFistt in ass pornLisbon portugal nightrlife sexBest refriigerators bottom freezerSoothe reed irritated facial skinNaahville puss + dirty thhe best ofFrrom tthe bottomm

oof my heart. DearWhores nakedSlut teen pussyPihtures oof stripers iin clubsLarge core breast biopsyBig ol tkts analFulll length free sexy climaxForce

peopole to have sexPurre pleasure cystal cityHot

and nked jon cenaNaked cougar picturesSpperm chlorePatrick andd luccas gayGroup anal sex ladiesAs fucked tthru

a gloryholeBeawch nude xxxYoung annd voluptuous girl

nudeTits ass pictures galleriesPicftures suck own boobUtube serm swapXxxx group sexx thumbnail moviesCherry poppens

interracial creampieFreee first anal seex movieWhat

a shit load of fuckJapanese gilrrs watchimg sexFreee junife leee sex comicAdut

dorothy outfitJimm prsntice gayy marriageLarge vintage leatherJoe skirt pornBttom

boy aBooty teen assKawaii shaved iceBlack lips stick pornLonhger streaming

pornWwww elephant vifeo hermaphrodute mmonster cofk hegre films Slovenkee porno slikeFemale miixed wrestling dominationVintage pre-1970 marblesNude gmyLinswday lown nudeFinal fantasy x2 yunaa pornPanrie fetish hairey pussyThumb sucking adultMoteel madee sex moviesCityy ggay mexico

tourGay guuy inn labrador cityRobin hooid erootic storiesSmall viegins nudeFreee erotic 3d artoon comicsBig tit blow job asianHow too sell a lebian bookReally sloppy cumshotsFather daughter ssex fantasiesNaughy histor vintage movieDr rx facial soapVarous tudor ssex scenesYouporn small boobsEblmy matue legsPaul mercurio gayTube

sexx nude styff freeHeer son’s reed bottomNudde streoscopic imageryNausea morning after sexGilliasn jaccobs lesbian kissFreee lesbian clkit sucking videosWomen wiith ttwo pussiesSubmnitted nude

girlfriendFree smokinng texas girl sexVintage amusment machinesFlat black bottomed bootsSaasy lesbosDes muklh eroticAsian geting fuckedWhho iis dik sutphenBody sscan nudeAmateur fedom ted tightFreee phat black milfsVrma

titsBreast augmenation omaha ne picturesGirs fucking girls moviesHp pavillion dv7-4080us daa dick fullXxxx internet

gamesOn line lesbiqn datingHuomor andd sexCovered iin goop

bukkakeHindu gayy fathersThick annd hairyAsian adies raakiAggressive gaay videoRedheazd xxxx sitesOldd bikini womanNuude naked

iin snowBlogg ccam sexyAsin dogbane saffe heapth benefitsPentouse nure

stewerdessesThee glass virginLesbien milfsSmokling jkint blowjobDisney in pornI want hoot sexNaked actresses wallpapers rarGayy daddy wikipediaMobile lessbian gangSexual risk assesssment scaleMetaloic lycra bikini

picsFacial hair picsFree dsi fcking moviesDownkoad frse podno movesEtra virgin new yorkBrpthers

and sisters sexual exLesbian spanked and abusedGreencomics adultGary+trish+byron sex swapping videosEklund breast diagramJessica

biel sexxy mmovie clipsXxxx insest momsHery tnomas nakedAdylt movike database

reviewsLutherean adult educationWashroom ssex

pornTeenn designerBdssm tipLyrics imm juust

a simple everyday normal moter fuckerInnocfent naked storyAsin yatchinng venturesSexy onee piede swimwaerFaith

leon fucking machineTeen voyeur clipsFreee fetiksh porn nno registrationLesbian pegsBreazst everr largest sizeBobby

sexAsian culture clothing informationConnecticut live seex clubsOnion booty sex clipsTeen pussy

holePicturees of girrls bare nakedBbbw granny tibe vidsYoyng naked chinese girls and

picturesAtlasnta georgia esfort bbbjElectric azor too penis stimulationSunvalley adultTwin falls

teen jobsJaps suckDvd pornn sharng freeHott teen orgasmingGodd oof wine andd pleasure inn ancient greeceForced upskirtAmatteur euroboysVirginiia ssex offenders informationDouble

breastewd coatJapaese oold man fuck youn girlHot gay

collage guys fuckingPuerta vllarta gayy hotelsGermawny sexual assault rateWatch pirn and penetrationAsian bigg tit blowjobsVooyeur fre changing

room videoHott horny drippong matuure babesSlutt aitSexy

dating servce indonesiaStatkte facial creamVintrage

flyibg sacer lampSmellks likoe tewen sirit yearHott babe bustyBittorent slutSun onn assGirls woth glassees haing sexToronto

passions escortFreee xxx intage streamKentucky stzte

sexual predator picture jeff meae jrChoises gold teenSexxy creeam

pieWitch tunes pornoOlld cubt holesDoont emjinem fucck giv i yric stillFrree bigg brreast blacksVintawge legwarmersChristfina aguilera nude freeFree amwteur hairy milf picturesNakd pjctures of vigggo

mortensenMther daughter fuckng same guy slutloadTeen maania

2Naked girlss onn thhe beanchHenery annd junbe lingerie

Tadalafilo 5 Mg Precio En Farmacias

Should you tell you be mistaken.

Cialis 5 mg prezzo cialis prezzo tadalafil 5 mg prezzo

cat casino официальный сайт

7sps.ru

Wow that was odd. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Anyways, just wanted to say wonderful blog!

lucky 88 pokies real money

Wow, superb blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is magnificent, let alone the content!

play bonus bears

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find the majority of your post’s to be exactly I’m looking for. Does one offer guest writers to write content in your case? I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on most of the subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome blog!

fire joker slot erfahrungen

It’s remarkable to go to see this website and reading the views of all mates about this post, while I am also eager of getting knowledge.

allwin plataforma login

Thank you for every other magnificent article. Where else may just anybody get that type of information in such a perfect method of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am on the search for such info.

melhor horario para jogar na lobo888

What’s up it’s me, I am also visiting this site on a regular basis, this website is actually pleasant and the users are truly sharing nice thoughts.

grupo telegram aviator betnacional

Hi there to every one, it’s actually a nice for me to pay a quick visit this site, it consists of helpful Information.

1win lucky jet как выиграть

Не упустите возможность воспользоваться выгодными ценами на Монтаж гипсокартона в Алматы. Закажите услугу уже сегодня и убедитесь в профессионализме наших мастеров!

Thank you for every other informative website. The place else could I am getting that type of info written in such a perfect manner? I have a mission that I am simply now running on, and I have been at the glance out for such info.

hellspin online casino real money

Pretty! This has been an incredibly wonderful article. Thanks for providing these details.

best online casinos for usa

Hello, I want to subscribe for this weblog to get latest updates, therefore where can i do it please help out.

play aviator casino

I got this web site from my pal who shared with me concerning this web page and at the moment this time I am browsing this site and reading very informative content at this place.

888 casino crazy time

гранд вегас казино с выводом

игровые автоматы vegas grand на деньги на iphone рубли

Соединительная муфта 3ПСТ-10-300/400 купить в Краснодаре

]Новые автоматы на деньги

Лучшие слоты на деньги

PA Speakers

Ribbon Microphones

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I am shocked why this twist of fate didn’t took place earlier! I bookmarked it.

https://clients1.google.com.kw/url?sa=t&url=https://didvirtualnumbers.com/de/

Great website you have here but I was wondering if you knew of any forums that cover the same topics talked about here? I’d really love to be a part of group where I can get advice from other knowledgeable people that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Appreciate it!

http://maps.google.com.tr/url?q=https://hottelecom.biz/id/

I am final, I am sorry, but this answer does not approach me. Who else, what can prompt?

Подробно расскажем, как Взыскать долг по расписке – Галичский районный суд Костромской области онлайн или самостоятельно Взыскать долг по расписке – Галичский районный суд Костромской области Взыскать долг по расписке – Галичский районный суд Костромской области онлайн или самостоятельно

Que Es Cialis

I am sorry, it at all does not approach me.

Cialis 5 mg prezzo prezzo cialis 5 mg originale in farmacia tadalafil 5 mg prezzo

#Best #site #awords:

koop een virtueel telefoonnummer

koop een virtueel telefoonnummer

Aviator Spribe играть на рубли казино

Добро пожаловать в захватывающий мир авиаторов! Aviator – это увлекательная игра, которая позволит вам окунуться в атмосферу боевых действий на небе. Необычные графика и захватывающий сюжет сделают ваше путешествие по воздуху неповторимым.

Aviator Spribe казино регистрация

Aviator Spribe отзывы казино

Добро пожаловать в захватывающий мир авиаторов! Aviator – это увлекательная игра, которая позволит вам окунуться в атмосферу боевых действий на небе. Необычные графика и захватывающий сюжет сделают ваше путешествие по воздуху неповторимым.

Aviator Spribe казино регистрация

Howdy exceptional website! Does running a blog similar to this require a great deal of work? I have virtually no knowledge of programming but I was hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyway, if you have any recommendations or tips for new blog owners please share. I know this is off topic however I just wanted to ask. Cheers!

Rybelsus

Hey! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog. Is it hard to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any tips or suggestions? Cheers

Мережева кнопка масленного обігрівача

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful article. Thank you for supplying this info.

Rybelsus

Hi to every single one, it’s truly a good for me to visit this web site, it consists of important Information.

C Tubas

Гайд по проекту Grass, Руководство по проекту Grass

займ без

займ на карту

Aviator Spribe играть на рубли казино

Добро пожаловать в захватывающий мир авиаторов! Aviator – это увлекательная игра, которая позволит вам окунуться в атмосферу боевых действий на небе. Необычные графика и захватывающий сюжет сделают ваше путешествие по воздуху неповторимым.

Aviator Spribe казино играть на тенге

гама казино

gama casino сайт

гама казино

gama casino

регистрация кэт казино

кэт казино

Heya this is kinda of off topic but I was wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding experience so I wanted to get guidance from someone with experience. Any help would be enormously appreciated!

https://partner-msk.ru

Производимые торгово-промышленным объединением тренажеры для кинезитерапии https://trenazhery-dlya-kineziterapii.ru и специально разработаны для восстановления после травм. Устройства имеют оптимальное соотношение стоимости и функциональности.

Предлагаем очень недорого аналог МТБ 2 с облегченной конструкцией. В каталоге интернет-магазина для кинезитерапии всегда в реализации варианты грузоблочного и нагружаемого типа.

Изготавливаемые тренажеры для реабилитации гарантируют комфортную и безопасную тренировку, что особенно важно для пациентов в процессе восстановления.

Конструкции обладают регулируемым сопротивлением и уровнями нагрузки, что позволяет индивидуализировать силовые тренировки в соответствии с задачами любого больного.

Все модели актуальны для кинезитерапии по рекомендациям врача физиотерапевта Сергея Бубновского. Оснащены ручками для комфортного выполнения тяг сидя или стоя.

Hmm is anyone else encountering problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to figure out if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any responses would be greatly appreciated.

аренда виртуального номера

I’m not sure exactly why but this blog is loading very slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a problem on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

http://ilban.garvigee.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=83801

Helpful information. Fortunate me I found your website by chance, and I am stunned why this coincidence didn’t took place in advance! I bookmarked it.

Гама казино

Hey there! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Fairly certain he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

Гама казино

Wow, marvelous blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is excellent, as well as the content!

http://www.stmcu.co.kr/gn/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=1511536

Российский изготовитель реализует тренировочные диски на сайте diski-dlya-shtang.ru для круглосуточной эксплуатации в коммерческих спортивных залах и в домашних условиях. Завод из России создает блины разного посадочного диаметра и любого востребованного веса для разборных штанг и гантелей. Рекомендуем к приобретению прорезиненные тренировочные диски для силовых тренировок. Они не скользят, не шумят и менее травматичны. Производимые изделия не нуждаются в постоянном обслуживании и ориентированы на длительную эксплуатацию в клубах. Рекомендуем большой каталог бамперных дисков с любым типом защитного покрытия. Приобретите веса с подходящей массой и посадочным диаметром по доступным ценам напрямую у российского завода.

Доброго всем дня!

Приобретите диплом Гознака с гарантированной подлинностью и доставкой по всей России без предоплаты.

http://saksx-attestats.ru/

У нас вы можете заказать документы об образовании всех ВУЗов России с доставкой по РФ и оплатой после получения – просто и удобно!

Наши услуги позволят вам купить диплом ВУЗа с доставкой по России без предоплаты и с полной уверенностью в его подлинности – просто и удобно!

Доброго всем дня!

Вы когда-нибудь писали диплом в сжатые сроки? Это очень ответственно и тяжело, но нужно не сдаваться и делать учебные процессы, чем Я и занимаюсь)

Тем кто умеет разбираться и гуглить информацию, это действительно помогает по ходу согласований и написания диплома, не нужно тратить время на библиотеки или встречи с дипломным руководителем, вот здесь есть хорошие данные для заказа и написания дипломов и курсовых с гарантией и доставкой по России, можете посмотреть здесь , проверено!

http://inmeta.ru/wd/sf/viewtopic.php?f=17&t=1103

купить аттестат

купить аттестат школы

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом техникума

купить диплом ссср

Желаю каждому нужных оценок!

[url=https://prednisonekx.online/]prednisolone prednisone[/url]

Приветики!

Было ли у вас когда-нибудь такое, что приходилось писать дипломную работу в сжатые сроки? Это действительно требует огромной ответственности и напряженных усилий, но важно не сдаваться и продолжать активно заниматься учебными процессами, чем я и занимаюсь.

Для тех, кто умеет искать и анализировать информацию в интернете, это действительно помогает в процессе согласования и написания дипломной работы. Не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или организацию встреч с дипломным руководителем. Здесь представлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями по ссылке , проверено!

https://glowsubs.ru/forum/topic/add/forum2/#postform

купить диплом техникума

купить диплом

купить диплом колледжа

купить диплом Вуза

купить диплом института

Желаю каждому положительных отметок!

Добрый день всем!

Вы когда-нибудь писали диплом в сжатые сроки? Это очень ответственно и тяжело, но нужно не сдаваться и делать учебные процессы, чем Я и занимаюсь)

Тем кто умеет разбираться и гуглить информацию, это действительно помогает по ходу согласований и написания диплома, не нужно тратить время на библиотеки или встречи с дипломным руководителем, вот здесь есть хорошие данные для заказа и написания дипломов и курсовых с гарантией и доставкой по России, можете посмотреть здесь , проверено!

http://ya.10bb.ru/viewtopic.php?id=3026#p5586

купить аттестат школы

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом цена

купить диплом бакалавра

купить диплом ссср

Желаю любому отличных оценок!

Добрый день всем!

Бывали ли у вас случаи, когда приходилось писать дипломную работу в крайне сжатые сроки? Это действительно требует большой ответственности и напряженного труда, но важно не унывать и продолжать активно участвовать в учебном процессе, как я и делаю.

Для тех, кто умеет эффективно находить и использовать информацию в интернете, это может существенно облегчить процесс согласования и написания дипломной работы. Больше не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или организацию встреч с научным руководителем. Здесь, на этом ресурсе, предоставлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по всей России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями на , это проверено!

http://pc2163.com/viewtopic.php?t=241666

купить диплом

купить диплом нового образца

купить диплом техникума

купить диплом ссср

купить диплом института

Желаю всем нужных оценок!

Приветики!

Были ли у вас случаи, когда приходилось писать дипломную работу в крайне ограниченные сроки? Это действительно требует большой ответственности и трудоемкости, но важно не отступать и продолжать активно участвовать в учебном процессе, как я.

Для тех, кто умеет эффективно находить и использовать информацию в сети, это действительно помогает в процессе согласования и написания дипломной работы. Больше не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или организацию встреч с научным руководителем. Здесь, на этом ресурсе, предоставлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по всей России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями тут , это проверенный источник!

http://links.musicnotch.com/otpluann7942

купить аттестат

купить диплом о среднем образовании

купить диплом магистра

купить диплом института

купить диплом нового образца

Желаю любому прекрасных оценок!

Добрый день всем!

Бывало ли у вас такое, что приходилось писать дипломную работу в крайне сжатые сроки? Это действительно требует огромной ответственности и напряженных усилий, но важно не опускать руки и продолжать активно заниматься учебными процессами, как я.

Для тех, кто умеет быстро находить и анализировать информацию в сети, это действительно помогает в процессе согласования и написания дипломной работы. Больше не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или устраивать встречи с дипломным руководителем. Здесь, на этом ресурсе, предоставлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по всей России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями на сайте , это проверено!

https://nc750.ru/member.php?u=2812

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом колледжа

купить диплом магистра

купить диплом университета

купить диплом техникума

Желаю каждому прекрасных оценок!

Здравствуйте!

Было ли у вас когда-нибудь так, что приходилось писать дипломную работу в очень сжатые сроки? Это действительно требует огромной ответственности и может быть очень тяжело, но важно не опускать руки и продолжать активно заниматься учебными процессами, как я.

Для тех, кто умеет быстро находить и использовать информацию в интернете, это действительно облегчает процесс согласования и написания дипломной работы. Больше не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или устраивать встречи с научным руководителем. Здесь, на этом ресурсе, предоставлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по всей России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями на сайте , это проверено!

https://theblogsharing.com/%d0%ba%d1%83%d0%bf%d0%b8%d1%82%d1%8c-%d0%b4%d0%b8%d0%bf%d0%bb%d0%be%d0%bc-%d0%be-%d1%81%d1%80%d0%b5%d0%b4%d0%bd%d0%b5%d0%bc-%d0%be%d0%b1%d1%80%d0%b0%d0%b7%d0%be%d0%b2%d0%b0%d0%bd%d0%b8%d0%b8-%d0%ba/

купить диплом Вуза

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом института

купить аттестат школы

купить аттестат

Желаю каждому пятерошных) отметок!

It’s a game. Five dollars is free. Try it It’s not an easy game

->-> 토토사이트.COM

super saver pharmacy

Добрый день всем!

Было ли у вас когда-нибудь так, что приходилось писать дипломную работу в очень сжатые сроки? Это действительно требует огромной ответственности и может быть очень тяжело, но важно не опускать руки и продолжать активно заниматься учебными процессами, как я.

Для тех, кто умеет быстро находить и использовать информацию в интернете, это действительно облегчает процесс согласования и написания дипломной работы. Больше не нужно тратить время на посещение библиотек или устраивать встречи с научным руководителем. Здесь, на этом ресурсе, предоставлены надежные данные для заказа и написания дипломных и курсовых работ с гарантией качества и доставкой по всей России. Можете ознакомиться с предложениями на сайте , это проверено!

https://cncsolesurvivor.com/forum/profile/bobbyec3093963/

купить диплом ссср

купить диплом в Москве

купить диплом цена

купить диплом бакалавра

купить диплом о среднем специальном

Желаю любому пятерошных) оценок!

Привет, дорогой читатель!

купить диплом института

Желаю каждому прекрасных отметок!

http://fulltheme.ru/viewtopic.php?f=33&t=12838

купить диплом в Москве

купить диплом нового образца

купить диплом цена

Доброго всем дня!

купить диплом Гознак

Желаю всем положительных оценок!

http://mail.webco.by/forum/viewtopic.php?f=81&t=27595

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом Вуза

купить диплом о среднем образовании

Здравствуйте!

купить диплом института

Желаю всем нужных оценок!

http://drahthaar-forum.ru/topic9211.html

купить диплом магистра

купить диплом бакалавра

купить аттестат

Hi there friends, its impressive article concerning cultureand entirely explained, keep it up all the time.

#be#jk3#jk#jk#JK##

купить американский номер телефона

Здравствуйте!

купить диплом нового образца

Желаю всем положительных оценок!

https://library.pilxt.com/index.php?action=profile;area=showposts;sa=messages;u=52454

купить диплом в Москве

купить диплом о высшем образовании

купить диплом бакалавра

В современном мире, где диплом становится началом удачной карьеры в любой области, многие ищут максимально быстрый путь получения образования. Факт наличия документа об образовании сложно переоценить. Ведь диплом открывает дверь перед людьми, стремящимися начать профессиональную деятельность или продолжить обучение в ВУЗе.

Предлагаем максимально быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы имеете возможность купить диплом нового или старого образца, и это является удачным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить обучение или утратил документ. Каждый диплом изготавливается с особой тщательностью, вниманием к мельчайшим деталям, чтобы на выходе получился 100% оригинальный документ.

Превосходство такого решения состоит не только в том, что вы сможете максимально быстро получить свой диплом. Процесс организовывается удобно, с нашей поддержкой. Начиная от выбора нужного образца документа до консультаций по заполнению персональной информации и доставки по стране — все под абсолютным контролем наших мастеров.

В результате, для всех, кто пытается найти быстрый и простой способ получения требуемого документа, наша услуга предлагает отличное решение. Купить диплом – это значит избежать продолжительного процесса обучения и сразу переходить к достижению собственных целей, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или старт профессиональной карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

В нашем мире, где диплом – это начало удачной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый путь получения качественного образования. Необходимость наличия официального документа об образовании переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь диплом открывает двери перед всеми, кто желает начать трудовую деятельность или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

В данном контексте наша компания предлагает оперативно получить этот важный документ. Вы имеете возможность приобрести диплом, что является выгодным решением для человека, который не смог завершить образование или утратил документ. Все дипломы производятся аккуратно, с особым вниманием ко всем элементам. На выходе вы сможете получить документ, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Преимущество данного подхода заключается не только в том, что вы сможете максимально быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организовывается комфортно, с нашей поддержкой. От выбора необходимого образца документа до консультаций по заполнению персональной информации и доставки по России — все будет находиться под абсолютным контролем наших мастеров.

В результате, для тех, кто ищет максимально быстрый способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания готова предложить отличное решение. Купить диплом – значит избежать продолжительного процесса обучения и сразу перейти к достижению личных целей, будь то поступление в университет или старт карьеры.

https://diploman-russiyans.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом становится началом отличной карьеры в любой отрасли, многие ищут максимально быстрый путь получения качественного образования. Наличие документа об образовании переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь именно он открывает двери перед каждым человеком, который собирается вступить в профессиональное сообщество или учиться в университете.

Мы предлагаем максимально быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы можете купить диплом старого или нового образца, и это становится отличным решением для человека, который не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием к мельчайшим элементам. В итоге вы сможете получить документ, максимально соответствующий оригиналу.

Преимущество подобного подхода состоит не только в том, что можно быстро получить диплом. Процесс организовывается просто и легко, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начав от выбора нужного образца документа до точного заполнения персональных данных и доставки в любое место России — все под абсолютным контролем наших специалистов.

Всем, кто ищет оперативный способ получить требуемый документ, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Приобрести диплом – значит избежать длительного процесса обучения и сразу перейти к своим целям, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или начало карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом становится началом отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально простой путь получения качественного образования. Факт наличия документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь именно диплом открывает двери перед любым человеком, желающим вступить в профессиональное сообщество или продолжить обучение в университете.

Наша компания предлагает оперативно получить этот важный документ. Вы сможете заказать диплом, и это является выгодным решением для человека, который не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. Каждый диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с особым вниманием к мельчайшим деталям, чтобы в итоге получился 100% оригинальный документ.

Превосходство подобного подхода заключается не только в том, что можно максимально быстро получить диплом. Процесс организовывается удобно, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начав от выбора требуемого образца документа до точного заполнения персональных данных и доставки по России — все будет находиться под абсолютным контролем наших специалистов.

Для всех, кто пытается найти быстрый и простой способ получения необходимого документа, наша услуга предлагает выгодное решение. Заказать диплом – значит избежать долгого процесса обучения и не теряя времени перейти к достижению собственных целей, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или старт успешной карьеры.

https://dlplomanrussian.com

В нашем мире, где диплом – это начало отличной карьеры в любой сфере, многие ищут максимально простой путь получения образования. Важность наличия официального документа сложно переоценить. Ведь именно диплом открывает дверь перед людьми, желающими вступить в сообщество профессионалов или учиться в университете.

В данном контексте мы предлагаем оперативно получить любой необходимый документ. Вы можете заказать диплом нового или старого образца, что будет выгодным решением для человека, который не смог завершить образование или утратил документ. диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием ко всем деталям. В итоге вы сможете получить 100% оригинальный документ.

Превосходство подобного подхода состоит не только в том, что вы оперативно получите свой диплом. Процесс организован комфортно, с нашей поддержкой. От выбора подходящего образца до точного заполнения персональной информации и доставки по России — все находится под полным контролем квалифицированных мастеров.

Для тех, кто ищет оперативный способ получения необходимого документа, наша компания предлагает выгодное решение. Купить диплом – это значит избежать продолжительного обучения и сразу переходить к достижению своих целей: к поступлению в университет или к началу трудовой карьеры.

https://diploman-russiyan.com

Сегодня, когда диплом становится началом успешной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Факт наличия официального документа об образовании переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь именно диплом открывает дверь перед каждым человеком, который хочет начать профессиональную деятельность или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

В данном контексте мы предлагаем очень быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы можете купить диплом старого или нового образца, и это становится отличным решением для человека, который не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием к мельчайшим деталям, чтобы в итоге получился полностью оригинальный документ.

Преимущество этого подхода состоит не только в том, что вы максимально быстро получите диплом. Весь процесс организован комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начав от выбора требуемого образца до консультации по заполнению личных данных и доставки по России — все находится под абсолютным контролем наших специалистов.

В результате, для тех, кто ищет оперативный способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Приобрести диплом – это значит избежать длительного процесса обучения и не теряя времени перейти к личным целям, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или старт трудовой карьеры.

https://diplomanc-russia24.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом – это начало успешной карьеры в любой отрасли, многие ищут максимально простой путь получения образования. Наличие документа об образовании сложно переоценить. Ведь именно диплом открывает дверь перед каждым человеком, желающим начать трудовую деятельность или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

В данном контексте наша компания предлагает быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы можете заказать диплом старого или нового образца, что является удачным решением для человека, который не смог закончить обучение или утратил документ. Все дипломы изготавливаются аккуратно, с особым вниманием ко всем элементам. На выходе вы получите полностью оригинальный документ.

Превосходство подобного подхода состоит не только в том, что вы сможете быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организован удобно, с нашей поддержкой. От выбора нужного образца до консультации по заполнению личной информации и доставки в любой регион страны — все будет находиться под абсолютным контролем опытных специалистов.

В результате, для всех, кто ищет быстрый и простой способ получения требуемого документа, наша услуга предлагает отличное решение. Заказать диплом – это значит избежать долгого обучения и не теряя времени перейти к личным целям: к поступлению в университет или к началу удачной карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом – это начало отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие пытаются найти максимально быстрый путь получения образования. Наличие официального документа трудно переоценить. Ведь диплом открывает двери перед людьми, желающими начать профессиональную деятельность или продолжить обучение в высшем учебном заведении.

В данном контексте мы предлагаем максимально быстро получить этот необходимый документ. Вы сможете приобрести диплом нового или старого образца, и это будет удачным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. Все дипломы изготавливаются с особой тщательностью, вниманием к мельчайшим деталям, чтобы в итоге получился продукт, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Превосходство подобного решения заключается не только в том, что вы сможете быстро получить диплом. Весь процесс организовывается просто и легко, с нашей поддержкой. Начиная от выбора требуемого образца до консультации по заполнению персональной информации и доставки в любое место России — все находится под полным контролем опытных мастеров.

Всем, кто ищет быстрый способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания готова предложить выгодное решение. Приобрести диплом – это значит избежать долгого обучения и не теряя времени перейти к достижению своих целей, будь то поступление в университет или старт карьеры.

https://diplomanc-russia24.com

В современном мире, где диплом – это начало отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Наличие официального документа трудно переоценить. Ведь диплом открывает двери перед каждым человеком, желающим вступить в сообщество профессиональных специалистов или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

В данном контексте наша компания предлагает оперативно получить этот важный документ. Вы можете купить диплом старого или нового образца, что является удачным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить образование, утратил документ или хочет исправить свои оценки. диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с особым вниманием к мельчайшим элементам, чтобы на выходе получился продукт, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Преимущество данного решения заключается не только в том, что можно быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организован удобно, с нашей поддержкой. От выбора необходимого образца до консультации по заполнению личной информации и доставки по России — все будет находиться под полным контролем качественных специалистов.

Для всех, кто хочет найти быстрый способ получения необходимого документа, наша компания может предложить выгодное решение. Заказать диплом – это значит избежать долгого процесса обучения и сразу переходить к достижению своих целей: к поступлению в университет или к началу удачной карьеры.

https://diploman-russiyans.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом становится началом успешной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально простой путь получения качественного образования. Факт наличия официального документа об образовании переоценить невозможно. Ведь именно он открывает дверь перед людьми, стремящимися начать трудовую деятельность или продолжить обучение в каком-либо университете.

Мы предлагаем оперативно получить этот необходимый документ. Вы имеете возможность заказать диплом нового или старого образца, и это становится отличным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить обучение или утратил документ. диплом изготавливается с особой тщательностью, вниманием к мельчайшим элементам, чтобы в результате получился полностью оригинальный документ.

Преимущество данного решения состоит не только в том, что можно максимально быстро получить свой диплом. Процесс организован удобно, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начиная от выбора подходящего образца до консультации по заполнению личных данных и доставки по стране — все находится под полным контролем наших специалистов.

Для тех, кто ищет быстрый и простой способ получить требуемый документ, наша компания предлагает выгодное решение. Приобрести диплом – это значит избежать долгого обучения и сразу перейти к достижению собственных целей: к поступлению в университет или к началу удачной карьеры.

https://diplomanc-russia24.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом – это начало успешной карьеры в любом направлении, многие стараются найти максимально быстрый и простой путь получения качественного образования. Важность наличия официального документа сложно переоценить. Ведь именно он открывает дверь перед каждым человеком, желающим вступить в профессиональное сообщество или продолжить обучение в университете.

Мы предлагаем оперативно получить этот необходимый документ. Вы сможете купить диплом нового или старого образца, и это будет отличным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. Все дипломы изготавливаются аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием ко всем нюансам. На выходе вы сможете получить 100% оригинальный документ.

Преимущества такого решения состоят не только в том, что вы максимально быстро получите диплом. Весь процесс организовывается комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. От выбора нужного образца до грамотного заполнения личных данных и доставки по России — все будет находиться под полным контролем наших специалистов.

Для всех, кто хочет найти быстрый способ получения необходимого документа, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Купить диплом – это значит избежать долгого обучения и сразу перейти к достижению своих целей, будь то поступление в университет или старт карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

В нашем обществе, где диплом становится началом отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Наличие документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь диплом открывает дверь перед всеми, кто стремится вступить в сообщество профессионалов или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

Предлагаем оперативно получить этот важный документ. Вы имеете возможность приобрести диплом старого или нового образца, что становится выгодным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить образование, утратил документ или хочет исправить свои оценки. дипломы производятся аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием к мельчайшим нюансам. В итоге вы сможете получить продукт, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Плюсы подобного подхода заключаются не только в том, что можно максимально быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организовывается комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. От выбора нужного образца до консультаций по заполнению персональных данных и доставки в любой регион России — все находится под абсолютным контролем опытных специалистов.

Таким образом, для тех, кто пытается найти максимально быстрый способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Заказать диплом – значит избежать длительного процесса обучения и сразу перейти к своим целям, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или старт удачной карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

Сегодня, когда диплом становится началом удачной карьеры в любой сфере, многие стараются найти максимально простой путь получения качественного образования. Факт наличия документа об образовании переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь диплом открывает дверь перед всеми, кто собирается вступить в сообщество квалифицированных специалистов или продолжить обучение в университете.

Предлагаем максимально быстро получить этот необходимый документ. Вы сможете приобрести диплом старого или нового образца, что будет выгодным решением для человека, который не смог закончить обучение или потерял документ. Все дипломы выпускаются с особой аккуратностью, вниманием ко всем деталям. В результате вы сможете получить документ, полностью соответствующий оригиналу.

Преимущества такого решения состоят не только в том, что вы сможете максимально быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организовывается комфортно, с нашей поддержкой. Начиная от выбора требуемого образца диплома до консультации по заполнению персональных данных и доставки по стране — все будет находиться под полным контролем наших специалистов.

Таким образом, для тех, кто пытается найти максимально быстрый способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания готова предложить выгодное решение. Купить диплом – значит избежать продолжительного процесса обучения и не теряя времени переходить к своим целям: к поступлению в ВУЗ или к началу удачной карьеры.

https://diploman-rossiya.com

В современном мире, где диплом – это начало успешной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Наличие официального документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь именно он открывает дверь перед всеми, кто желает вступить в сообщество профессиональных специалистов или продолжить обучение в университете.

Наша компания предлагает быстро получить любой необходимый документ. Вы имеете возможность купить диплом, и это становится отличным решением для всех, кто не смог завершить образование, потерял документ или хочет исправить свои оценки. дипломы изготавливаются с особой тщательностью, вниманием к мельчайшим элементам. В результате вы получите 100% оригинальный документ.

Преимущество подобного решения заключается не только в том, что вы максимально быстро получите диплом. Весь процесс организовывается комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начав от выбора подходящего образца диплома до консультаций по заполнению личной информации и доставки в любое место России — все под полным контролем наших специалистов.

Для тех, кто хочет найти быстрый и простой способ получить требуемый документ, наша услуга предлагает отличное решение. Купить диплом – это значит избежать длительного процесса обучения и сразу перейти к достижению личных целей: к поступлению в ВУЗ или к началу удачной карьеры.

https://dlplomanrussian.com

В современном мире, где диплом – это начало отличной карьеры в любой сфере, многие ищут максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Наличие документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь именно он открывает двери перед каждым человеком, который желает начать трудовую деятельность или учиться в высшем учебном заведении.

Наша компания предлагает максимально быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы сможете приобрести диплом старого или нового образца, что является отличным решением для всех, кто не смог закончить образование, утратил документ или желает исправить плохие оценки. Каждый диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с особым вниманием ко всем нюансам. На выходе вы получите документ, максимально соответствующий оригиналу.

Превосходство подобного подхода состоит не только в том, что вы сможете быстро получить диплом. Процесс организован комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. Начав от выбора необходимого образца до консультации по заполнению личных данных и доставки в любой регион России — все будет находиться под полным контролем качественных специалистов.

Всем, кто пытается найти быстрый способ получения необходимого документа, наша услуга предлагает отличное решение. Приобрести диплом – это значит избежать длительного процесса обучения и сразу переходить к своим целям, будь то поступление в университет или начало карьеры.

https://diplomanc-russia24.com

prednisone buy no prescription

worldwide pharmacy online

Fantastic post however I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Cheers!

https://images.google.ms/url?q=https://nephewspade1.bravejournal.net/sklo-dlia-far-vidminna-iakist-i-vigidna-tsina

Whats up are using WordPress for your blog platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and set up my own. Do you require any html coding expertise to make your own blog? Any help would be really appreciated!

https://blogfreely.net/sandurnjvz/h1-b-kupiti-novii-korpus-dlia-fari-iak-pravil-no-pidibrati-b-h1

Pretty! This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing this info.

https://zenwriting.net/fastofldxm/h1-b-korpus-i-sklo-far-iak-voni-vplivaiut-na-osvitlennia-dorogi-b-h1

В нашем мире, где диплом является началом отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально быстрый путь получения образования. Необходимость наличия официального документа об образовании трудно переоценить. Ведь именно он открывает двери перед каждым человеком, желающим вступить в сообщество профессиональных специалистов или учиться в каком-либо институте.

В данном контексте мы предлагаем очень быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы имеете возможность купить диплом, и это будет удачным решением для человека, который не смог завершить обучение, потерял документ или хочет исправить свои оценки. дипломы производятся аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием к мельчайшим элементам. В итоге вы получите документ, 100% соответствующий оригиналу.

Преимущества данного решения заключаются не только в том, что вы сможете максимально быстро получить диплом. Весь процесс организовывается удобно и легко, с нашей поддержкой. От выбора необходимого образца диплома до правильного заполнения личной информации и доставки в любой регион страны — все под абсолютным контролем наших мастеров.

Для тех, кто ищет быстрый и простой способ получения требуемого документа, наша компания может предложить отличное решение. Приобрести диплом – значит избежать длительного обучения и не теряя времени перейти к своим целям: к поступлению в ВУЗ или к началу удачной карьеры.

diploman-russia.com

В современном мире, где диплом становится началом отличной карьеры в любой отрасли, многие пытаются найти максимально быстрый и простой путь получения образования. Наличие документа об образовании переоценить попросту невозможно. Ведь именно диплом открывает дверь перед любым человеком, который стремится вступить в сообщество профессиональных специалистов или учиться в ВУЗе.

Наша компания предлагает максимально быстро получить этот важный документ. Вы можете заказать диплом, что становится отличным решением для человека, который не смог завершить обучение, утратил документ или желает исправить плохие оценки. дипломы производятся аккуратно, с максимальным вниманием к мельчайшим элементам, чтобы в результате получился полностью оригинальный документ.

Плюсы такого подхода состоят не только в том, что можно максимально быстро получить диплом. Процесс организовывается комфортно, с профессиональной поддержкой. От выбора необходимого образца диплома до консультаций по заполнению персональной информации и доставки по России — все будет находиться под абсолютным контролем качественных специалистов.

Для всех, кто хочет найти максимально быстрый способ получить необходимый документ, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Купить диплом – это значит избежать продолжительного обучения и сразу переходить к личным целям, будь то поступление в ВУЗ или начало карьеры.

https://www.diploman-russiyan.com/

Сегодня, когда диплом является началом отличной карьеры в любом направлении, многие ищут максимально простой путь получения качественного образования. Наличие официального документа об образовании переоценить невозможно. Ведь именно он открывает двери перед всеми, кто хочет вступить в профессиональное сообщество или продолжить обучение в ВУЗе.

В данном контексте наша компания предлагает оперативно получить этот необходимый документ. Вы можете приобрести диплом старого или нового образца, и это становится удачным решением для всех, кто не смог завершить обучение, утратил документ или желает исправить плохие оценки. диплом изготавливается аккуратно, с особым вниманием к мельчайшим нюансам. На выходе вы получите полностью оригинальный документ.

Превосходство данного решения заключается не только в том, что можно быстро получить свой диплом. Весь процесс организовывается просто и легко, с нашей поддержкой. Начиная от выбора нужного образца до правильного заполнения персональной информации и доставки по стране — все под полным контролем наших мастеров.

В результате, для тех, кто пытается найти быстрый и простой способ получения необходимого документа, наша компания предлагает отличное решение. Купить диплом – значит избежать долгого обучения и сразу переходить к достижению своих целей: к поступлению в университет или к началу трудовой карьеры.

http://www.diplomanc-russia24.com