Our Debt-Capacity Fishery

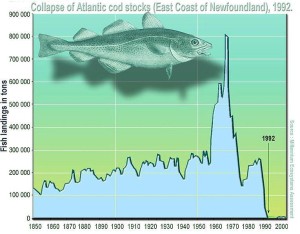

Environmental economists have a useful framework to analyze limited but renewable resources. It is called maximum sustainable yield. For a fishery, it measures the number of fish that can be harvested each year without impairing the future viability of the fishery. Violate this level long enough and you have the case of the Grand Banks cod population that was overfished for decades until it completely collapsed in 1992. Usefully, these economists also bring a long-term perspective (a VERY long-term perspective), which is critical to understand systemic problems that compound over generations.

The intergenerational management of limited resources provides a perfect framework to understand our national debt problem.

In the fishery analogy, our recent experience of trillion-dollar budget deficits is the annual catch. Entitlements like Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and now Obamacare, represent commitments to increase the fish catch in the future. The present value of those unfunded future commitments totals about $66 trillion and combined with existing debt brings us to a grand total of $84 trillion. To be clear, this is the amount of future generations’ debt capacity we have already used up assuming the budget is balanced every year in the future.

It is important to note that our debt-capacity fishery is not as static as the Grand Banks. It expands with economic growth and contracts with recessions. So can we grow our fishery fast enough so that the maximum sustainable yield (new debt issuance) can increase to finance $66 trillion in commitments?

The recent report by the Social Security and Medicare trustees is instructive on this question. The current cost of these programs is about 8.7 percent of GDP. The trustees forecast those costs to increase to 11.8 percent of GDP by 2035 and 12.7 percent by 2087. Clearly, these cost burdens are expected to grow much faster than GDP. We are in the same place as the cod industry in 1959, (See chart) looking at the cods landings of 200,000 tons that year and naïvely expecting to increase the take to 800,000 tons annually without any adverse impact on the fishery.

What about that “trust fund reserve” locked away in that lockbox Al Gore made famous in the 2000 election? Unfortunately, the only asset in the lockbox is $3 trillion in IOUs from the treasury. So in reality, this represents a use of our fishery capacity not an addition to it. Those bonds will need to be paid by future taxpayers, as the funds are needed to pay the committed benefits.

Why can’t we just increase taxes to improve the situation? Increasing taxes only adds to capacity if there is actually a reduction in debt. This is the same as reducing the annual fish catch to let the fish population rebuild. A tax increase of that magnitude, going from 18 to 24 percent of GDP, would most certainly impair future economic growth reducing our debt-capacity despite possible higher current tax revenue.

One might argue that instead of borrowing more money we can always just print more. After all, the greenback is still the world’s reserve currency and likely to remain so. That process is already underway with the Fed buying bonds from the treasury and increasing the monetary base a whopping $2.6 trillion in the last 12 months. With a couple steps in between, this is not much different than Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe calling up De La Rue to order a few more tons of banknotes. Increasing that monetary base is not an asset but rather, a liability of the government.

When my Dad was born the U.S. had issued and outstanding debt of $2,789 per person (all these amounts are in constant 2013 dollars). When I was born that number had increased to $8,895. In between, of course, were the Great Depression and WWII. Debt per person peaked in 1946 at $11,758. The WWII generation worked hard to keep it under control and the individual’s share of the federal debt burden declined from 1946 until 1967.

Then the Vietnam War and LBJ’s Great Society changed the direction permanently except for a brief respite during the effective collaboration of President Clinton and the Republican controlled House in the late 1990s. When my youngest children were born in the 1990s the debt per capita had risen to $29,605. Today it is $51,710, an increase of 1,854 percent in only two generations.

In some ways our debt capacity seems unlimited. After all, the Chinese grumble sometimes but still seem happy to buy our bonds. But will they have the kindness to fund the $66 trillion we will need in the future? Can’t the FED just print more money to buy up those bonds? Certainly true, but at some point the value of the dollar declines and inflation increases to a Zimbabwean scale.

On some level we hope that even the mostly innumerate politicians inside the beltway would agree that there is some limit to our children’s debt capacity. We have depleted their fishery to an extraordinary degree over the last 20 years. The only way to replenish it is to dramatically cut entitlements.

Many cities and states have reached that conclusion, swallowing a difficult political pill and putting in place plans to reduce their own unfunded liabilities. To get to that point with Federal entitlements will require strong leadership, a long-term perspective and intestinal fortitude – characteristics not much in evidence in Washington today.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

It’s a game. Five dollars is free. Try it It’s not an easy game

->-> 토토사이트.COM